Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman once spent an afternoon together. They drank elderberry wine and talked about being famous. From The New Republic.

By David M. Friedman

On January 31, 1882, a partially paralyzed man living with his brother and sister-in-law in a row house in Camden, New Jersey, wrote to a friend to tell him of a recent visitor to that home. “He is a fine large handsome youngster,” the man wrote of that guest. And “he had the good sense to take a great fancy to me.”

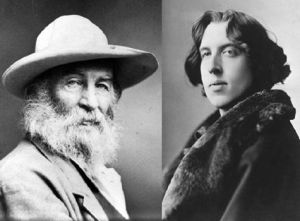

Thus Walt Whitman described the day he spent with Oscar Wilde. This meeting between the self-described “old rough” who revolutionized American poetry with his masterpiece Leaves of Grass and the self-anointed “Professor of Aesthetics” who was touring America with a lecture praising sconces and embroidered pillows, has been examined often in the intervening years, usually through the lens of what is now called queer history, or as an interesting, if not particularly consequential, moment in the history of literature.

But neither approach takes the true measure of the meeting’s importance. For Wilde didn’t travel to Camden to talk about gender roles or belles lettres. The writer was still years away from becoming the author whose peerlessly witty plays are still staged today. What drew him to Whitman’s home was the opportunity to discuss fame. He wanted to listen to the singer of “Song of Myself”—an older man (Whitman was 62, Wilde 27) with inexhaustible energy, despite his infirmity, for self-promotion. Whitman was an international icon who exploited the fuzzy line between acclaim and notoriety and a media-savvy poet who understood the crucial role of image in the making of a literary career. Wilde didn’t travel to Camden to learn how to be a famous writer. That, he was certain, he would later teach himself. He went to learn how to be a famous person. It would be hard to imagine a more apt pairing of teacher and student.

Wilde had been sent to America by Richard D’Oyly Carte, the business manager for Gilbert & Sullivan, whose latest operetta, Patience, had recently opened in the English capital to rave reviews and huge ticket sales. Carte had dispatched his clients’ previous hits to America, where they were well-received. He planned to do the same with Patience, but he was nervous. Patience was a satire of the British aesthetic movement, a movement united behind the slogan “art for art’s sake.”1

“The most beautiful things in the world are the most useless: peacocks and lilies, for instance,” the Oxford professor John Ruskin had written.

Aesthetes championed the use of decorative ornamentation in the making of furniture, ceramics, textiles, and so on, and proclaimed the superiority of handmade goods to mass-produced ones. Its poetic credo was summed up by Keats: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

To W.S. Gilbert, however, the movement was a nirvana for useless narcissists and a way for self-adoring dandies to natter away in public about their exquisite taste, a conviction he verbalized to great comic effect in Patience. The principal male roles in the operetta, Bunthorne and Grosvenor, two poets competing for the hand of a lass named Patience, were composites modeled on several leading aesthetes, among them: the painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti and James McNeill Whistler, the poet Algernon Swinburne, and the recent Oxford graduate Oscar Wilde—who claimed, with no justification, to be the leader of the movement. Wilde had just self-published his first book of poetry to some withering reviews, sarcastic cartoons in humor magazines such as Punch, and negligible sales.

What had made Carte nervous was that the aesthete was not a native species in the United States. Would American audiences get the jokes? A solution was put forth by the manager of Carte’s New York office: send over a “real” aesthete (maybe Oscar Wilde?) and have him present a series of lectures in America (“On Beauty,” perhaps?), delivered in the same “aesthetic” costume (satin breeches, shiny patent-leather pumps, form-fitting velvet jacket, and so on), worn by Bunthorne in Patience. A telegram was sent from New York to Wilde in London that claimed (falsely) that fifty American lecture agents were ready to book him, if he were available to speak. Wilde was nearly broke, so he answered, “Yes, if offer good.” It was: fifty percent of the box-office take, less expenses.

Wilde arrived on January 3, 1882, and, six days later, presented his first lecture, titled “The English Renaissance of Art,” to a sold-out house at Chickering Hall (seating capacity: 1,250) on lower Fifth Avenue. That a man virtually unknown to most Americans could achieve that commercial triumph was, in large part, the result of the nearly nonstop coverage in the New York press of Wilde’s preening at parties in the nights before his lecture by leading figures in Manhattan society. “I stand [in] the reception rooms when I go out, and for two hours they defile past for introduction,” Wilde wrote of his socializing in New York to a friend in London. “I bow graciously and sometimes honour them with a royal observation.”

A reporter from Philadelphia interviewed Wilde as they took a train to that city, the second stop on his tour. “What poet do you most admire in America?” the reporter asked Wilde, who had won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for poetry, at Oxford.2

Past winners included Matthew Arnold and John Ruskin.

“I think Walt Whitman and [Ralph Waldo] Emerson have given the world more than anyone else,” he answered. “I do so hope to meet Mr. Whitman,” (Perhaps Wilde’s press agent had informed him that the poet lived nearby.) “I admire him intensely,” Wilde continued. “Dante Rossetti, [Algernon] Swinburne, William Morris and I often discuss him.” In reality, Swinburne and Wilde were mere acquaintances and had not often discussed anything. But that didn’t stop Wilde from adding, as if he were repeating something from their “frequent” discussions: “There is something so Greek and sane about [Whitman’s] poetry; it is so universal, so comprehensive.” After these words were published in the Philadelphia Press, Wilde got the response he was likely hoping for. Whitman sent this note to his hotel: “Walt Whitman will be in from 2 till 3 ½ this afternoon & will be most happy to see Mr. Wilde.”

“I come as a poet to call upon a poet,” Wilde said, when Whitman opened his door. Whitman, who adored being adored as few others ever have, was delighted to hear this. He went to the cupboard and removed a bottle of his sister-in-law Louisa’s homemade elderberry wine. The two men began to empty it.

They were unlikely drinking companions. Wilde had a double “first” from one of the most prestigious universities in the world; Whitman left school at age eleven. Wilde was a polished talker and epigrammist; Whitman spoke in short, occasionally ungrammatical bursts. Wilde was a snob; Whitman (in his own words) “talk[ed] readily with niggers.” Despite these differences, the two men enjoyed each other’s company. “I will call you Oscar,” Whitman said. “I like that so much,” Wilde replied. He was thrilled to be in such close proximity to the man who, as Wilde had hoped to do for himself, had launched his career with a self-published book of poems.

So Wilde accepted Whitman’s invitation to accompany him to his den on the third floor, where, as Whitman said, they could be on “thee and thou terms.” Wilde was shocked by the tiny room where Whitman wrote his verse. Dust was everywhere, and the only place for Wilde to sit, a low stool near Whitman’s desk, was covered by a messy pile of newspapers Whitman had saved because he was mentioned in them.

The American told his guest he admired the work of Britain’s poet laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, yet noted that it was often “perfumed … to an extreme of sweetness.” He then asked: “Are not you young fellows going to shove the established idols aside, Tennyson and the rest?”

“Tennyson’s rank is too well fixed,” Wilde said, “and we love him too much. But he has not allowed himself to be a part of the living world…. We, on the other hand, move in the very heart of today.” That “we” was the aesthetic movement. “You are young and ardent,” Whitman said, “and the field is wide, and if you want my advice, [I say] go ahead.”

The real subject of Whitman’s conversation wasn’t literary form; it was how to build a career in public, with all the display that self-glorifying achievement requires. We can deduce that with confidence because the first thing Whitman did when he reached his den was to give his guest a photograph of himself. Whitman had pioneered the idea that a writer in search of fame should fashion himself as a literary artifact. When Leaves of Grass was self-published in 1855 it did not have Whitman’s name on the title page; instead, it had his portrait on the preceding page, showing the author standing tall in workman’s garb, his collar open, his left hand in one pocket of his slacks, his right resting on his hip, his bearded head topped by a hat set at a cocky angle, and his eyes meeting the reader with a stare simultaneously casual and challenging. No writer had ever presented himself to the public this way, let alone so intentionally. (Or with a visible button fly.) This frontispiece is now considered, the scholars Ed Folsom and Charles M. Price write, “the most famous in literary history.”

The portrait Whitman gave Wilde in 1882 appeared on his next book, Specimen Days & Collect, an assemblage of travel diaries, nature writing, and Civil War reminiscences. (Whitman had spent the war years in Washington, working as a government clerk and volunteering as a hospital visitor.) He is in profile in the photograph, sitting in a wicker chair wearing a wide-brimmed hat, an open-necked shirt, and a cardigan. A butterfly is perched on his index finger, held in front of his face. “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies,” Whitman once told a friend. Years later Whitman’s “butterfly” was found in the Library of Congress. It was made of cardboard; it had been tied to his finger with string.

By handing Wilde that photo Whitman was teaching him that fame as a writer is only partly about literature. It is also about committing oneself to a performance. Such role-playing isn’t the act of a phony; in Whitman’s mind every pose he struck was authentic. This type of authenticity—the fashioning of an image one would be faithful to in public—Wilde had experienced on a small scale playing the aesthete on the campus of Oxford’s Magdalen College and at parties in London. It was instructive to have its truth verified by a literary star who had proved its efficacy on an international scale. Wilde had always believed there was nothing inglorious about seeking glory. By handing Wilde his portrait, Whitman was confirming that instinct.

Days before he met Whitman, Wilde sat for the photographer Napoleon Sarony in New York, posing himself as an aesthetic Adonis in satin breeches. Following Whitman’s lead, he used these portraits as his “logo” as he crossed America delivering his lectures. He would present more than 140 of them and remain in the States for a year, becoming the second-most-recognized Briton in America, behind only Queen Victoria. (Not bad for a writer who’d hardly written anything.)

“God bless you, Oscar,” Whitman said, when Wilde left. A Philadelphian joked that it must have been hard for Wilde to swallow the homemade wine Whitman had offered. For once Wilde rejected an invitation to snobbery. “If it had been vinegar, I should have drunk it all the same,” he said. “I have an admiration for that man which I can hardly express.”